Cinema has defined Pakistan in a way many other cultural phenomenas rarely are able to do, and that is by becoming the reflection of what our society has been until this stage. It has in many ways, explored dichotomies of life, while also facilitating fantasies with films that go beyond realities of existence.

However, what is has also given us, are more than seven decades of visual culture and material that one cannot help but explore in all of its nuances. The songs, the dance moves, the story lines, the iconic actors, and the cultural importance of it all, have defined a cinema industry like no other.

What did each of this tumultuous decade bring for the industry? Diva has the lowdown…

1940s — 1960s Pakistani Cinema’s Growing Pains

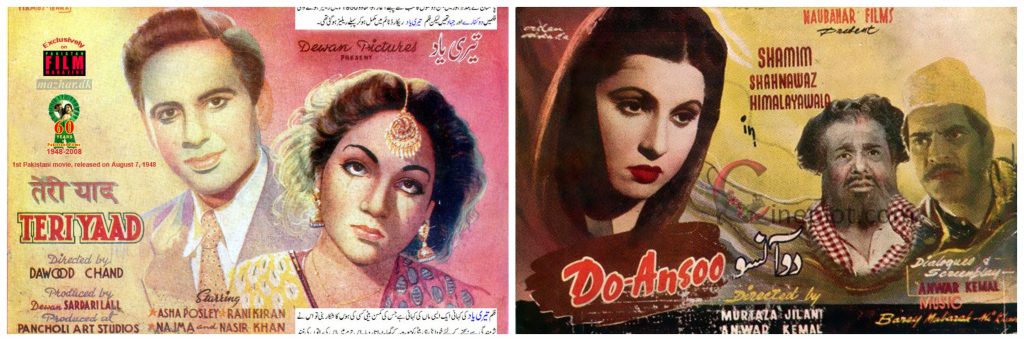

Despite Lahore seeing its first studio opening up a decade before Pakistan was carved out of India, the journey of ‘Pakistani’ cinema begins in 1947. Lahore became the hub of cinema in Pakistan, but upon independence, there was a shortage of funds and filming equipment, which initially paralysed the film industry. However, with all hardships faced, the first Pakistani feature film, Teri Yaad released a year after independence in Lahore. Over the next few years, films that were released reached mediocre success until the release of Do Ansoo in 1950. It went on to become the first film to attain a 25-week viewing making it the first film to reach silver jubilee status!

This upward climb continued with Pakistan’s nightingale, Madam Noor Jehan’s directorial debut Chanway being released in 1951. The film became the first to be directed by a female director in the country. The growth continued albeit not as strongly as expected, and the cinema viewership increased. It continued on to become a viable business, and by 1954, Eveready Pictures – the first major studio in Lahore reached golden jubilee status staying on screens for 50-weeks with a film it produced. This was also the time when legendary playback singer Ahmed Rushdi started his career in April 1955 after singing his super-popular first song in Pakistan ‘Bander Road Se Kemari‘.

1960s — 1970s Cinema Comes of Age

The 1960s marked the highest growth for Pakistani cinema, and that is why it is often cited as being the golden age. Many actors became ‘celebrities’ and never looked back. The Pakistani audiences were introduced to stars like Muhammad Ali, Waheed Murad, Zeba, Shabnam, Rani, and Nadeem, amongst others during this period who would go on to become cinema legends on the silver screen.

Cinema at this time was opening its roots to both local and international stories, and in 1962, even a film like Shaheed was released which introduced the Palestine conflict to Pakistanis in cinemas, becoming an instant hit. In September 1965, following the war between Pakistan and India, all Indian films were completely banned. Pakistani cinemas did not suffer much from the decision to remove the films and instead received better attendances.

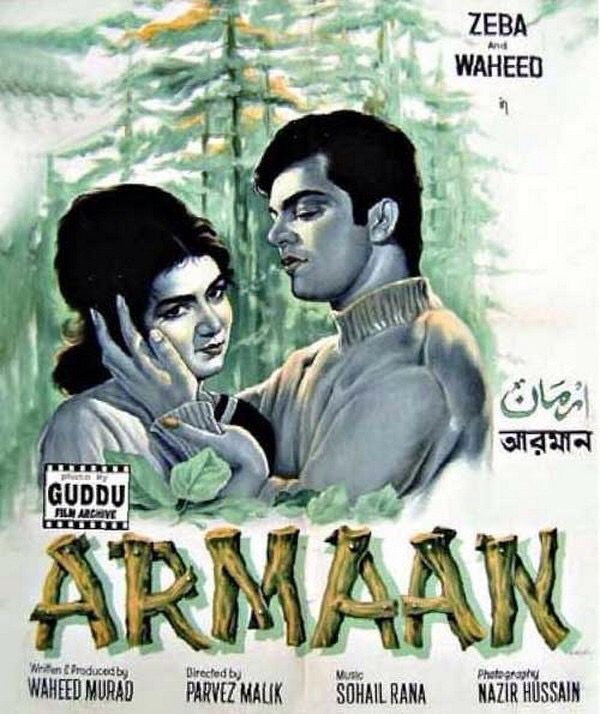

This is when the cult-classic film like Armaan was released and became one of the most cherished Urdu films to ever release. The film is said to have given birth to Pakistani pop music, by introducing playback singing legends like composer Sohail Rana and singer Ahmed Rushdi. The film became the first to complete a 75-week screening at cinemas throughout the country attaining a platinum jubilee status.

This growth continued towards the late 1960s and early 1970s, before political turmoil once again returned with the East Pakistan conflict brewing into a strife for independence.

1970s — 1980s Experimental Extravaganza and Other Stories

The 1970s began amidst concerns, yet some films did excellent businesses. The film Dosti, released in 1971 and turned out to be the first indigenous Urdu film to complete 101 weeks of success at the box office, dubbing it the first recipient of a Diamond Jubilee. Things soon started going towards political uncertainty and even took charge of the entertainment industry. Filmmakers were asked to consider sociopolitical impacts of their films as evident by the fact that the makers of Tehzeeb, a 1971 film, were asked to change the lyrics with a reference to Misr, Urdu for Egypt, that might prove detrimental to diplomatic relations of Egypt and Pakistan.

The 1970s began amidst concerns, yet some films did excellent businesses. The film Dosti, released in 1971 and turned out to be the first indigenous Urdu film to complete 101 weeks of success at the box office, dubbing it the first recipient of a Diamond Jubilee. Things soon started going towards political uncertainty and even took charge of the entertainment industry. Filmmakers were asked to consider sociopolitical impacts of their films as evident by the fact that the makers of Tehzeeb, a 1971 film, were asked to change the lyrics with a reference to Misr, Urdu for Egypt, that might prove detrimental to diplomatic relations of Egypt and Pakistan.

So vulnerable was the film industry to the changing political landscape that in 1976, an angry mob set fire to cinema in Quetta just before the release of the first Balochi film, Hamalo Mah Gunj. The experimental wave still continued, however, and Pakistan’s first ever English film, Javed Jabbar’s Beyond the Last Mountain, released in 1976, The Urdu version, Musafir did not do well at the box office, though.

The same decade also brought forward the first decline of Pakistani cinema as well. During the regime of Zia-ul-Haq (1978-1988), the islamization of the country hit. One of the first victims of this sociopolitical change was Pakistani cinema. Imposition of new registration laws for film producers requiring filmmakers to be degree holders, where not many were, led to a steep decline in the workings of the industry. The government forcibly closed most of the cinemas in Lahore. New tax rates were introduced, further decreasing cinema attendances.

The dark horse of the era was the film, Aina, though, releasing in 1977. It marked a distinct symbolic break between the liberal Zulfikar Ali Bhutto years and the increasingly conservative and revolutionary Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq regime. The film stayed in cinemas for over 400 weeks, with its last screening at ‘Scala’ in Karachi where it ran for more than four years. To date, it is considered the most popular Pakistani film ever.

Films dropped from a total output of 98 in 1979, of which 42 were in Urdu, to only 58 films of which 26 were in Urdu in 1980, hinting towards the new era of Punjabi film takeover.

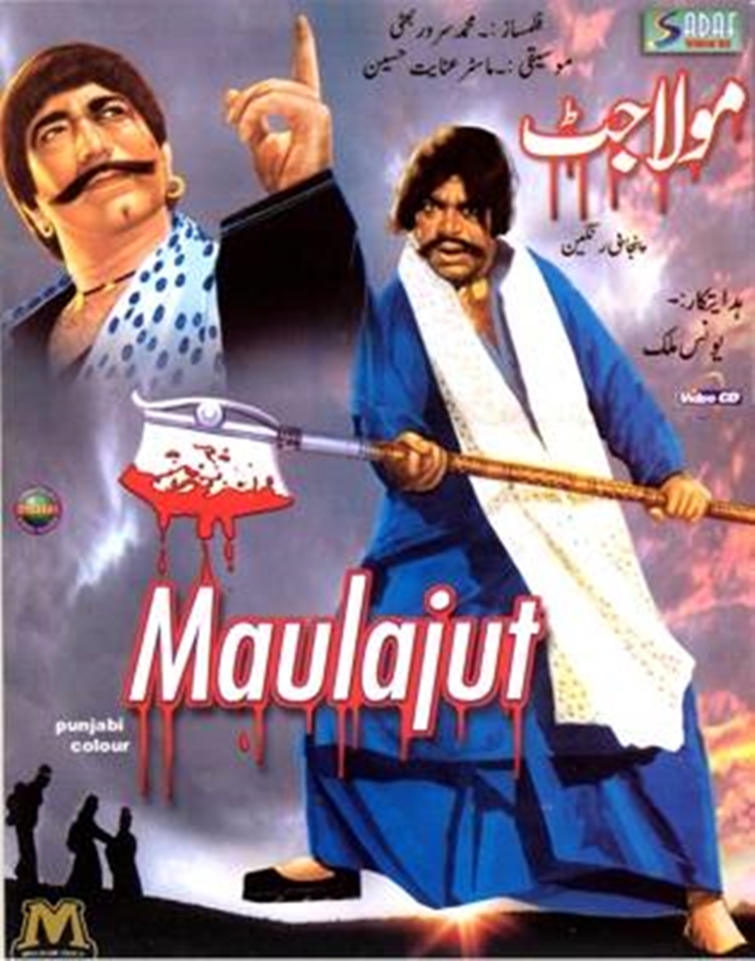

1980s — 1990s The Punjabi Film Invasion

The film industry by now was on the verge of collapse as people began turning away from Urdu cinema. The filmmakers that remained in the industry, produced super hits like Punjabi cult classic Maula Jatt in 1979, telling the story of a gandasa-carrying protagonist waging a blood-feud with a local gangster. Growing censorship policies against displays of affection, rather than violence, came as a blow to the industry. As a result, violence-ridden Punjabi films prevailed and overshadowed Urdu cinema.

This film sub-culture came to be known as the gandasa culture. In Punjabi cinema Sultan Rahi and Anjuman became iconic figures of this culture. The once romantic and lovable image of Pakistani cinema in the 1960s and 1970s had transformed into a culture of violence and vulgarity by the 1980s.

In 1983, legendary actor Waheed Murad died and was yet another blow to the cinema industry. This enthusiasm soon disappeared and not even Pakistan’s first science fiction film, Shaani, in 1989, directed by Saeed Rizvi employing elaborate special effects, could save the fate of the Pakistani film industry.

1990s — 2000s The Downfall of Lollywood

At the start of the 1990s, the Pakistani film industry’s future already looked gloomy. From the several dozen studios across the country, only eleven were operational. By now the annual output dropped to around 40 films, all produced by a single studio. Other productions would be independent of any studio usually financed by the filmmakers themselves.

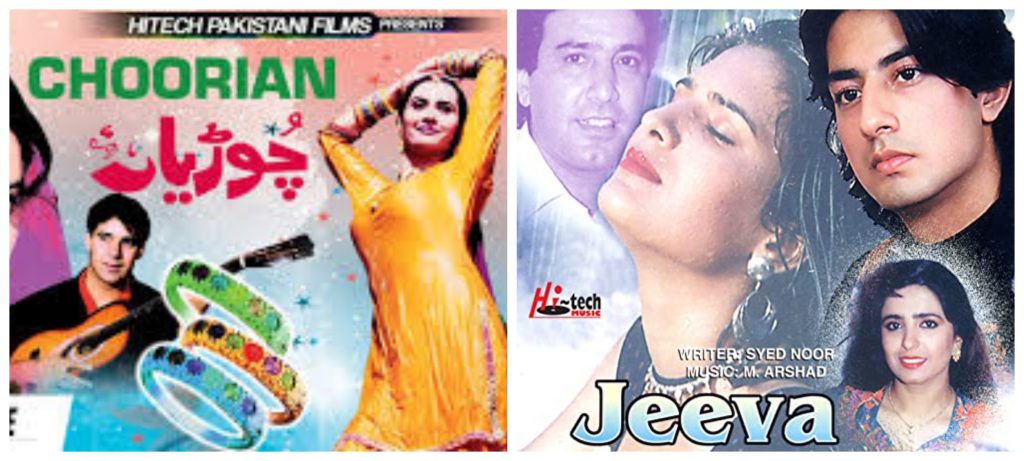

The last decade of the 20th century did bring new talent into the industry, however. Names like Shaan, Moammar Rana, Saleem Shaikh, Faysal Quraishi, Reema, Meera, Resham, Neeli amongst others became increasingly popular. The films were seen as a mix of Bollywood-inspired films, stereotypical plots from old films, and of course the continuation of the Punjabi cinema style of film.

At the same time, controversy raged over the 1998 film Jinnah, produced by Akbar Salahuddin Ahmed and directed by Jamil Dehlavi. Objections were raised over the choice of actor Christopher Lee as the protagonist depicting Muhammad Ali Jinnah and inclusion of Indian Shashi Kapoor as archangel Gabriel in the cast combined with the experimental nature of the script. The film did however, go on to become a hit cult-classic.

Other hits were Syed Noor’s 1995 film Jeeva, Saeed Rizvi’s paranormal Sarkata Insaan and his 1997 film Tilismi Jazira. 1998 saw the release of Noor’s Choorian, a Punjabi film that grossed Rs180 million rupees and for the longest time remained Pakistan’s highest-grossing film.

The industry was pronounced dead by the start of the new millennium. By the early 2000s the industry failed to even churn out more than two films a year.

2000s – 2010s Stagnant Cinema

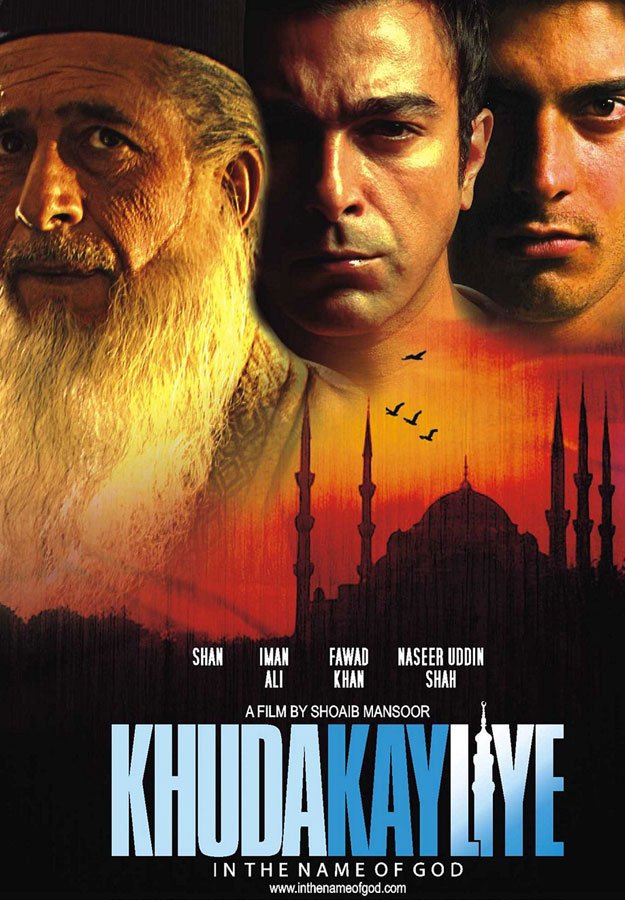

Lollywood by now had given the audiences nothing that was considered likeable. By 2005, a gradual shift had begun whereby Karachi was replacing Lahore as the film hub of the country. Many film makers, producers, directors shifted to Karachi to avail new opportunities. In August 2007, Shoaib Mansoor directed and released Khuda Kay Liye, which became an instant success and was touted as the film that ‘revived’ cinema.

Lollywood by now had given the audiences nothing that was considered likeable. By 2005, a gradual shift had begun whereby Karachi was replacing Lahore as the film hub of the country. Many film makers, producers, directors shifted to Karachi to avail new opportunities. In August 2007, Shoaib Mansoor directed and released Khuda Kay Liye, which became an instant success and was touted as the film that ‘revived’ cinema.

Despite optimism of a solid revival, progress continued to be slow. Several films were released after Khuda Kay Liye, which saw limited success including Shaan Shahid’s directorial project Chup, Syed Noor’s Price of Honor, Iqbal Kashmiri’s Devdas and Son of Pakistan, Syed Faisal Bukhari’s Saltanat, Reema Khan’s Love Mein Ghum, and Mehreen Jabbar’s Ramchand Pakistani.

None were able to stimulate the audiences, until Shoaib Mansoor’s luck struck again with Bol.

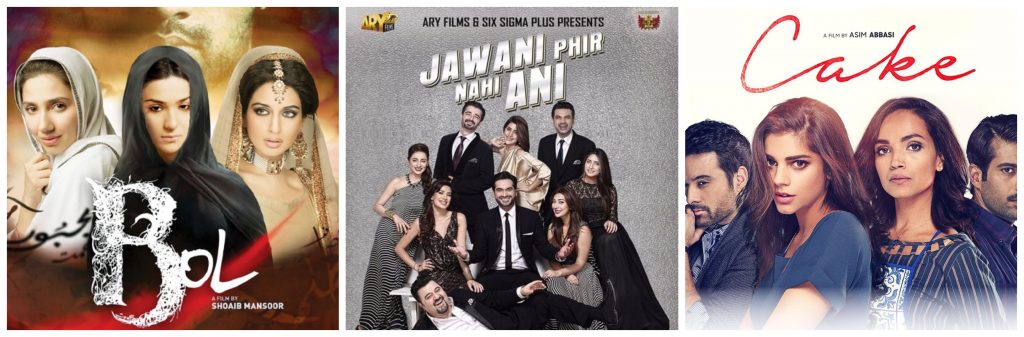

2010s – 2020 The New Wave of Pakistani Cinema

Shoaib Mansoor’s Bol seemed to have officially revived the cinema of Pakistan, and years after the film, brought many new narratives to the cinema. Since 2011, films continued standing out as box office successes, which included films like Waar, Na Maloom Afraad, Jawani Phir Nahi Ani, Actor in Law, Bin Roye, Punjab Nahi Jaungi, Cake, Parwaaz Hai Junoon, amongst others.

Shoaib Mansoor’s Bol seemed to have officially revived the cinema of Pakistan, and years after the film, brought many new narratives to the cinema. Since 2011, films continued standing out as box office successes, which included films like Waar, Na Maloom Afraad, Jawani Phir Nahi Ani, Actor in Law, Bin Roye, Punjab Nahi Jaungi, Cake, Parwaaz Hai Junoon, amongst others.

At the same time, Pakistani filmmakers ventured into different genres, even releasing the first 3D computer animated adventure film in the country, 3 Bahadur by Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy. It was the first instalment in the franchise of animated film series. The same year saw some of the most critical acclaimed Pakistani films being released, including Moor and Manto.

The years since then have continued to be extremely successful, and the industry now has managed to release a number of blockbuster films each year that have even been released internationally. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, 2020 was reported to be one of the biggest years for Pakistani film releases. However, given the situation most films will now be releasing in the newly-started decade, starting from 2021.

Have anything to add to the story? Tell us in the comment section below.